China’s Belt and Road Initiative Is Not Debt Trap Diplomacy

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/charts-of-the-week-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative/

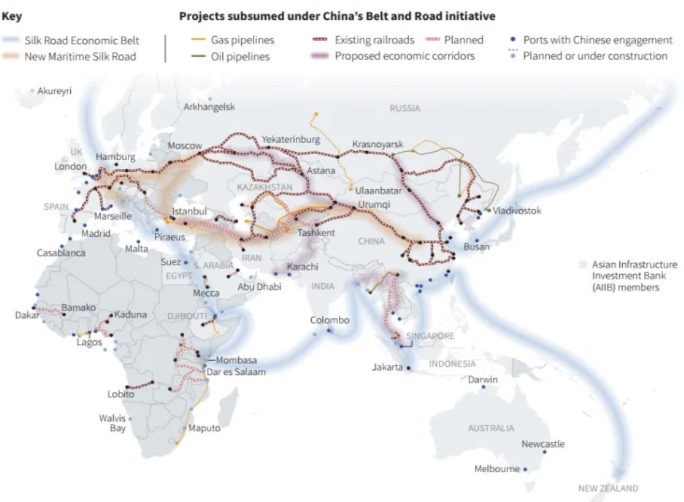

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s ambitious foreign policy to foster infrastructure and economic development and to create a trade network with China as the central hub. Founded in 2013, the BRI partners with third-world and developing nations and provides loans to fund infrastructure and economic stimulus projects. However, despite numerous successful economic ventures, a few unsuccessful BRI projects have inaccurately shifted the third-world perspective of the BRI from mutually beneficial to predatory debt-trap diplomacy. Many Western scholars argue that rather than for the advertised purpose of producing positive economic contributions in their partner countries, the BRI is instead an opportunity for China to take advantage of the economic instability in third-world countries. In reality, there is no evidence of China purposely bankrupting BRI countries to achieve a secret military or neo-colonial agenda. In fact, China has been a net economic benefit to the majority of BRI countries. To overcome this perceived predatory perspective of the BRI, China needs to be more involved in the management of funds in their partner countries, especially for developing countries with historically corrupt or unstable governments.

According to the debt-trap narrative, China first forces massive and unrealistic infrastructure financing loans on unsuspecting third-world countries and purposefully encourages them to pile up massive amounts of debt that are unlikely to be paid off. In doing so, China establishes a greater influence and leverage that it can use to exploit resources or build strategic military bases in those countries. The chief example used by critics is Sri Lanka’s failed Hambantota Port investment. By 2017, the port’s commercial performance was abysmal and incurred more than 300 million USD in losses on top of its 1.2 billion dollars of debt toward China. Unable to pay back Chinese loans, Sri Lankan President Sirisena arranged to write off their debt in exchange for the Chinese seizure of the port. Fears of the port becoming a secret military base erupted when the Sri Lankan port was visited by two Chinese attack submarines in 2015. With other failed and existing BRI projects in Southeast Asia like Cambodia and Laos, a pattern forms showing potential for total Chinese military control of the Indian Ocean and surrounding bodies of water.

The timeline presented above represents the conventional narrative presented by Western scholars and the media, which is very misleading for two key reasons. First, the Hambantota project was proposed not by China, but by the Sri Lankan government. As far back as 1970, Sri Lankan leadership developed a plan to build a second port in a region where the prime minister was facing growing political opposition and sought international investors. China agreed to provide a loan already devised by Sri Lanka.

Second, while the narrative indicates that the BRI’s malicious actions single-handedly caused Sri Lanka’s debt crisis, China is not Sri Lanka’s only creditor or even its biggest one by far. 81% of Sri Lanka’s foreign debt is held by the US and European institutions alongside other Western allies. From 2009 to 2016, Sri Lankan leadership continuously borrowed money from foreign markets for personal use, widening the country’s deficit and crippling the Sri Lankan economy. The total 1.3 billion USD loaned by the Chinese government made up only 4.8% of the country's total external debt. The BRI’s agreement with Sri Lanka to write off debt in exchange for equity in the port is portrayed as being the cause for Sri Lanka’s economic downfall, however, it is rather Western institutions alongside poor Sri Lankan governance that primarily led to Sri Lanka’s economic crisis.

China also frequently writes off debt or extends loans to partner BRI countries demonstrating a genuine Chinese desire for the economic success of these projects. China has restructured over 240 billion USD of debt owed by BRI countries. China also frequently provides additional credit and time to help BRI countries avoid defaulting on their loans with a key example being its 15 billion dollar credit to Mongolia for three years and the loan extension it granted Iraq.

Lastly, allegations of military base building have just as many flaws. The alleged “string of pearls” theory is a network of military facilities built through BRI asset seizure to expand China’s influence in the Indian Ocean. However, China has no interest in pushing countries toward debt traps, because it would financially cripple its own economy. In total, there have been just two instances where BRI countries have resorted to giving equity to China to write off their debt out of an estimated 1600 BRI projects. China also cannot afford to purposefully set up high-risk debt-traps. If every BRI country were meant to default on their loan, China would lose over 440 billion dollars of BRI investments across the world, severely damaging China’s own economy in the process.

Furthermore, China has even turned down requests to build military bases. Pakistan has repeatedly requested China to turn its BRI-financed Gwadar port into a naval base, yet China remained uninterested. According to the “string of pearls” theory, China should be jumping at the opportunity to build a military base in Pakistan which is a key location in the Indian Ocean, yet their disinterest alongside a lack of actual military bases being built or even any asset seizures reveals that the “string of pearls” theory is an unfounded conspiracy.

The few economic mishaps in the BRI’s track record have overshadowed its achievements and economic benefits provided to host countries. BRI projects stimulate local job growth and economic growth with a key example being Kenya’s Mombasa-Nairobi highway. The World Bank estimates that the BRI network countries will also receive significant increases in foreign direct investments from OECD countries, allowing them to expand their developing economy even further. These benefits, however, are often overshadowed.

Widespread fear-mongering of the debt-trap diplomacy narrative has significantly undermined the impact of the BRI and as a result, has dissuaded both current and other developing countries from partnering with China. In 2018, Pakistan and Myanmar significantly reduced their BRI loans by 2 million and 6 million respectively. Some countries like Sierra Leone and Malaysia have even scrapped projects completely. Unfortunately, this does not hurt China as much as it hurts the developing countries themselves.

China is being portrayed as the big bad villain, but it seems as though China is the only country willing to be the solution for these economically and politically unstable countries. For example, Cuba, which is under a trade embargo from the US and is excluded from most international lending sources, turned to China in need of economic development. In Africa, while OECD countries continue to focus the majority of their efforts on social services and humanitarian aid, China is perhaps the only lender that is addressing the continent’s 26 trillion USD gap in infrastructure financing. Western commercial banks are unwilling to make risky investments in economically unstable countries, so China is not only a proven alternative but a necessary one for third-world countries to grow.

The BRI backlash could counterintuitively be a good thing for the BRI. China is not intentionally debt-trapping its partner countries; however, China does need to make adjustments to its overall approach to dispel the perception of predatory ambition and relay China’s core desire for economic partnership. First, China should assure its partners that they will not resort to seizing strategic assets or any kind of equity exchange. Their actions in Sri Lanka, though not intentional nor desired by China, are the root of concern for developing countries. Second, China should be more involved in projects to avoid misuse or misallocation of funds. They must rethink the oversimplified belief that they can just give large sums of money to economically unstable countries and expect a scheduled return on investment. Lastly, China needs to clearly lay out to the countries it partners with what China is getting out of their deal, otherwise developing countries are only assuming the debt trap narrative presented to them. Greater Chinese involvement in the countries they partner with and more transparent interests will help shift the narrative back in the BRI’s favor.

The narrative of BRI debt-trap diplomacy is riddled with holes. Theories of purposeful debt trapping and advancing military agendas are based on a few failed economic ventures and undermine the BRI’s accomplishments. China genuinely seeks greater economic connectivity with countries in primarily Asia and Africa to present an alliance alternative to the US. However, Xi Jinping and the BRI’s ambitious vision will remain unfulfilled if misconceptions about the BRI continue to fester. Anti-BRI sentiment has driven potential partnerships away from the BRI and the project has suffered as a result. However, these concerns are not entirely unfounded. Developing countries’ fears of falling into massive piles of debt are legitimate and need to be addressed by the Chinese government if they want to see the future benefits of the BRI come to fruition.