Saul Goodman, redemption, and the value of radical kindness

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt11630828/mediaviewer/rm250613505/?ref_=tt_ov_i

Edited by Amelia Cantwell

Note: This article contains heavy spoilers for Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul.

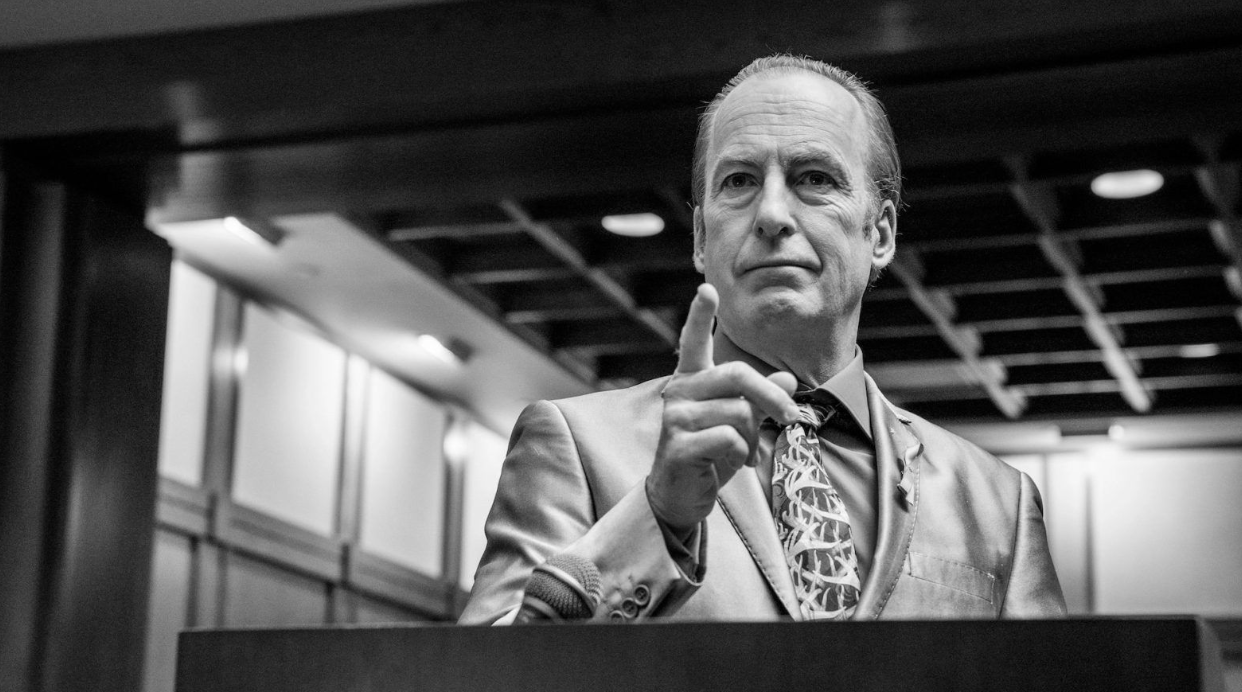

What does it mean to be redeemed? Better yet, what does it mean to be redeemable? The TV drama Better Call Saul takes these questions and runs with them, exploring something that Breaking Bad, its parent show, hadn’t quite gotten to. While both shows explore the potential for darkness in obsessive masculinity, unquestioning neoliberalism, and the cascading consequences of our choices, the main characters of Breaking Bad are faced mainly with death and escaping it, not truly considering the prospect of redemption. However, Better Call Saul’s criminal lawyer Jimmy McGill—who goes on to take the name Saul Goodman—grapples with these questions right into the series’ finale. While the show does not provide any outright answers for its audience, it offers a portrait of redemption that proves incredibly valuable for our current political moment.

In order for a person to be redeemable, it is, by definition, necessary to assume that they are able to change. While this may seem an easy enough assumption to accept, in practice, it is not always that consistent. For example, if I were to ask you to think of the worst person alive today and ask you whether you thought them capable of changing for the better, what would your answer be? And would your answer be the same had I asked you outside of the context of this article? How about right after that person had done something reprehensible? These are the sort of questions that Better Call Saul stress tests in its dynamic between Jimmy McGill and his older brother, Chuck.

While both Jimmy and Chuck are lawyers, their paths to the profession were starkly different, and this serves as a major source of tension throughout the show: Chuck went to U Penn and then to Georgetown Law Center before founding a successful law firm, whereas Jimmy was a con artist who went clean, getting a law degree from an online program and then seeking to establish his own legal practice. Despite ostensibly good intentions on Jimmy’s end—he serves as a public defender and a lawyer for the elderly—the brothers can’t quite shake the toxic dynamic that they’ve developed with one another. Chuck refuses to accept Jimmy’s new path as genuine because of his criminal past and tendency to bend the rules (“He’ll never change. Ever since he was 9, always the same”), and Jimmy internalizes his brother’s notion that he’ll never meaningfully change (“I’ll always be Chuck McGill’s loser brother”). This cycle sustains itself despite attempts from both brothers to break it, as encapsulated in this exchange in the final episode of the show: "Jimmy, if you don't like where you're heading, there's no shame in going back and changing your path." Jimmy responds, "When have you ever changed your path?”

When Chuck takes his own life halfway through the series as an unintended consequence of Jimmy damaging Chuck’s career, this leaves the brothers’ conflict unresolved, which only further cements Jimmy’s belief that he is thoroughly irredeemable. From this point on, Jimmy rejects therapy, cuts off his romantic partner Kim (the only person he’s shown even a hint of vulnerability to), and ultimately embraces the Saul Goodman persona: a criminal lawyer with no sense of shame, regret, or emotional authenticity. Eventually, Saul partners with meth kingpin Walter White, is forced to go into hiding when his drug enterprise collapses, and is charged in court with a litany of crimes. Despite the severity of his actions, Saul manages to obtain a plea deal of seven years in prison, down from the original sentencing recommendation of 86 years.

However, at the very last moment, Saul—or rather, James McGill, as he asks to be called in this scene—decides to own up to all of his crimes and reject the seven-year plea deal that he had originally obtained. Not only that, but he takes personal responsibility for the death of his brother: “I took away the one thing he lived for: the law. After that, he killed himself. It didn’t have to go that way. And I live with that.” Thus, the series ends with Jimmy McGill settling into a life sentence in federal prison, and the audience is left to interpret these events as they were shown.

Morality of the prison system itself aside, Jimmy’s reclamation of his identity and his willingness to take accountability here seem to be uncontroversial, moral goods. That said, was Jimmy McGill really redeemed in the end? This is quite a loaded question and only begets more questions about redemption as we consider it. Must redemption be motivated by doing what is right, or can someone act in a redeeming way with selfish aims in mind? Aside from being the right thing to do, Jimmy’s demonstration of accountability meant he’d be able to look Kim in the eyes again, a self-oriented motivation that might have meant more to him than his freedom. Furthermore, are there acts that are truly irredeemable? Jimmy made millions by engineering addictions and serving as an accessory to murder. Should these acts preclude redemption?

These are questions that we all need to consider, especially in light of tanking faith in the American judicial system, a consistent belief that America is in moral decline, and sharply polarized views on the death penalty. Thankfully, there are many different perspectives and tools we can use to assess cases like Jimmy’s, and one framework especially worth highlighting is radical kindness. Closely related to the psychological concept of unconditional positive regard and built on the recognition that people don’t act without reason, radical kindness advocates for unconditional empathy and support alongside accountability. It is important to note here that kindness is quite different from simple niceness—it doesn’t mean hollowly flattering everyone, but rather making the space to truly understand others and acting accordingly.

Radical kindness considered, how exactly does this help us look at Jimmy and broader questions of redemption? Considering that the show humanizes an otherwise disgusting character from Breaking Bad and lets us see him before he became Saul, it has already done half of the work for us by simply encouraging us to truly understand Jimmy. In seeing why he is the way that he is, his actions are no more excusable, but it’s far easier to see him as a human being just as vulnerable to terrible circumstances as the rest of us. While we almost never get this sort of insight into others in our real day-to-day lives, the kind of understanding that Better Call Saul offers its audience—that bad people tend to come from bad systems—cracks the door wide open to thinking about justice and redemption in much more nuanced ways and makes Jimmy’s decision to hold himself accountable when he didn’t need to all the more compelling. I don’t believe there’s such a thing as an irredeemably evil person, and you are free to disagree with me on that, but I urge you to consider and reconsider what makes a person redeemable in your eyes. After all, despite his glaring flaws, Chuck McGill hit on something quite valuable in saying, “There's no shame in going back and changing your path.”