How the Republican Revolution Broke Congress

When people today think about Congress, one word tends to come to their mind: dysfunctional. According to RealClearPolitics, in March 2009, Congress had only a net negative 15% disapproval rating. In the aftermath of the government shutdown in October 2013 that furloughed 800,000 workers and left 1.3 million without definite pay, congressional approval dipped to just 8.5% with 85% of the American public disapproving of the job Congress was doing. Even now, with Congress soon to be divided again, it has a net negative 48.2% disapproval rating. After another government shutdown at the beginning of 2018, independent Senator Angus King of Maine said that Congress was like “a high school football team that hasn’t won a game in five years. We’ve forgotten how to win.” King, who caucuses with Democrats similar to Vermont independent Bernie Sanders, echoes a common sentiment here.

Congress has become used to using continuing resolutions in place of passing its regular budgets, which are rarely, if ever, completed on time. King and Sanders’ colleagues from across the aisle like Lamar Alexander of Tennessee complain that “many of the new senators are unaware of the chamber’s most basic rules” due to the constant level of dysfunction and gridlock as there isn’t enough legislation on the floor of the Senate to teach members about these new rules. In the House, the Problem Solvers Caucus, a bipartisan group of congresspeople proposed a set of new rules in July 2018 that would allow rank-and-file members of the House to move more legislation onto the legislature’s floor. These new rules are designed to reduce gridlock while removing the ability of individual members of Congress to call for no-confidence votes in House leadership. To some degree, gridlock is built into the American political system, part of an effort by James Madison and other framers of the Constitution to disperse power. But more recent trends like partisan polarization, anti-establishment rhetoric, and a domination of party primaries by “activist” candidates intent on combating the other side have also made great contributions to this phenomenon.

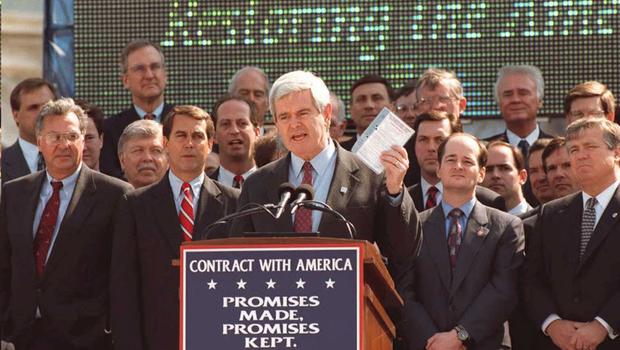

While the rise in congressional dysfunction has been a trend for quite some time, this latest acceleration, especially in partisan polarization, is something relatively recent. Many of the causes go back to the 1994 midterm elections, often nicknamed “The Republican Revolution.” Coming hot off the Republican Party’s electoral defeat in the 1992 presidential election to upstart Bill Clinton, Republicans rallied behind House Minority Whip Newt Gingrich to lead them to victory. Gingrich was a known firebrand in the House before being promoted to the Minority Whip position in 1988 and before the 1994 midterms drafted the “Contract with America.” This was a set of policy positions aimed at reducing the size of government through a balanced budget, tax cuts, and numerous reforms to the running of the House of Representatives. These policies were characteristic of Gingrich, who had used his bullhorn in House Republican leadership to “build a much more aggressive, activist party” that he thought was unafraid of turning politics into bloodsport. Gingrich was known for constantly lecturing his colleagues on how to aggressively combat their Democratic opponents based on their records. And when that failed, Gingrich, who viewed politics as a “war for power,”was known to say “when in doubt, Democrats lie.”

One of the big coincidences of Gingrich’s time in the House was, as Coppins points out in her The Atlantic article “The Man Who Broke Politics,” that after being elected while serving as a college professor in 1978, Gingrich entered the House in 1979, the same year that C-SPAN began to do live coverage of the House floor. Gingrich would give bombastic floor speeches to an empty chamber, well aware that viewers at home were being fed his fire and brimstone directly through their televisions. Four years later in 1983, Gingrich founded the Conservative Opportunity Society to develop goals for House conservatives. This group of right-wing members of the House Republican caucus had grown tired of what they viewed as ineffective party leadership. As current House Minority Whip, Steny Hoyer of Maryland detailed in 2009, “Gingrich’s proposition, and maybe accurately, was that as long as [Republican leaders] and our party cooperate with Democrats and get 20 or 30 percent of what we want and they get to say they solved the problem and had a bipartisan bill, there’s no incentive for the American people to change leadership. You have to confront, delay, and undermine and impose failure in order to move the public. To some degree, he was proven right in 1994.”

After the 1988 elections in which Republican George H. W. Bush was elected to the presidency, Democrats maintained their control of both houses of Congress, and maintained control of both chambers in 1990 and 1992. To counter this, Gingrich, now in House leadership, wrote a memo for his fellow House members and Republican congressional candidates titled “Language: A Key Mechanism for Control” that recommended that they refer to their Democratic opponents with words like “sick, pathetic, lie, anti-flag, traitors, radical,” and “corrupt.” He also encouraged them to frame battles in the media with Democrats as battles between good and evil, and to refer to media opponents as the “liberal media elite.” Going even further than many of his colleagues, Gingrich didn’t hesitate in drawing on conspiracy theories to advance his political goals. Gingrich used the suicide of Bill Clinton’s aide and longtime friend Vince Foster in 1993 as a talking point against the Clintons, including the conspiracy theory that Foster was killed in a coverup related to the Whitewater scandal. The result was a resounding success for Republicans: the 1994 midterms netted the party 54 seats in the House of Representatives and nine seats in the Senate, the first time that the party had controlled the House since 1955.

Newt Gingrich followed up his election to Speaker of the House of Representatives in 1995 with an attempt to swiftly implement the “Contract with America,” only to see much of it fall apart, as Coppins writes, due to either a lack of willingness in to pass the legislation in the Senate or due to presidential vetoes. Instead, Gingrich went about consolidating power in the office of Speaker of the House and reducing the power of institutions within the House of Representatives. Gingrich reduced the number of congressional committee and slashed committee staffs by a third while greatly restricting the power of committees, committee chairs, and caucuses to center power in the office of House Speaker. By reducing committee staffs, Gingrich reduced the amount of institutional knowledge and social capital in the House of Representatives in order to further consolidate his own power. Gingrich also put in place term limits for committee chairs, reducing the power of these chairs to contest with the Speaker while also removing a key strategy for rewarding loyalty and effective leadership for House members that also developed institutional knowledge for the holders of these positions.

Newt Gingrich not only reduced the institutional power of those below Speaker of the House, he also weakened the role that federalism and science played in informing House proceedings by eliminating the Office of Technology Assessment and the Advisory Committee on Intergovernmental Relations. Gingrich used his position as head of House Republicans to revolutionize fundraising, reducing the congressional workweek to 3 days in order to increase the amount of time that caucus members could spend raising money. According to Professor Lawrence Lessig, this helped turn the Republican caucus into a $1 billion fundraising behemoth, opening the floodgates for the rising influence of big donor dollars in Congress. This inspired Senators John McCain and Russ Feingold to begin writing the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act in 1995, which passed in 2002 and was struck down by the Citizens United ruling in 2010.

But Gingrich didn’t just use the Republican Revolution to erode congressional institutions. He also used it to increase the sense of negative partisanship in Congress as well. Gingrich adopted a hardline stance on the budgetary process with President Clinton, which some have reported as starting with the personal slight of Gingrich being kicked off of Air Force One on the way to the 1995 funeral of Israeli statesman Yitzhak Rabin. The resulted was two government shutdowns, one in November 1995 and then a second one in December to January 1995 to 1996 that furloughed 800,000 and 284,000 government employees, respectively, with the latter occurring at the height of the holiday season. Alan Abramowitz and Steven Webster recently reported that “one of the most important trends in American politics over the past several decades has been the rise of negative partisanship in the electorate.” One can see that much of this negative partisanship spawned with the Monica Lewinsky scandal in 1998, of which Gingrich made sure to take advantage.

The Lewinsky scandal proved to be a pivotal event for Gingrich’s speakership and for the Republican Party. Not only did it bolster the rise of right-wing media outlets (Drudge Report rose to prominence in 1998 on being the first news outlet to report on the scandal), it further helped Gingrich in his goal of nationalizing and balkanizing American politics. Gingrich’s rise to power was, as Coppins writes, aided by a recognition of the pattern that parties were increasingly aligning based on ideology and race, and not just geography or class, as had been the norm. A Southern Republican himself, Gingrich took advantage of this trend by using the Contract with America to nationalize the 1994 elections around Clinton’s presidency and to bring to an end the dominance of Democrats in the American South. In 1990, Democrats outnumbered Republicans 83 to 46 in the South in Congress, while after 1994 Republicans led Democrats 73 to 64 in the South.

Gingrich also used the nationalizing of elections to attack the institution of government itself. Leading up to the 1994 elections, Gingrich and his Republican allies brought the work of Congress to a virtual standstill in an effort to make governmental dysfunction an issue of the campaign. Even after the election, Gingrich and House Republican leaders openly disdained the idea of compromising with Clinton and House Democrats, attacking Clinton as a “tax and spend liberal.” According to Kellyanne Conway, then leading her own polling firm, “Long before there was ‘Drain the swamp,’ there was Newt’s ‘Throw the bums out.’” But before long, Gingrich himself was forced to make compromises with Clinton in order to pass a budget for the 1996 fiscal year. Then, amidst the fury of the Lewinsky scandal and Gingrich’s attempt to nationalize another midterm election, Democrats won 5 House seats, the first time this had happened in a midterm for the President’s party since 1934. Soon the very conservative bomb throwers that Gingrich had helped elect turned on Gingrich, forcing him to resign his speakership and his seat amidst an ethics investigation, with Gingrich calling those who had forced him out “cannibals.”

But the effects of the Republican Revolution did not end there. In the lead-up to the 1994 midterms amidst Gingrich’s forcing of gridlock on the United States Congress, future Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell referred to Gingrich’s strategy as giving “gridlock a good name.” McConnell, a major advocate of corporate speech and reducing barriers to the influence of moneyed donors in elections, has similarly pursued a strategy of eroding congressional institutions, but now in the Senate. He ridded the Senate of the 60-vote filibuster to push through the confirmation of Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch. McConnell and House Republican leaders also slowed the work of Congress to a halt prior to the 2010 midterm elections in order to attack congressional dysfunction and gridlock in the lead-up to the elections. This came at the same time that Republican leadership attacked government elites in an attempt to curry the populist backlash of the Tea Party movement in a way that set the stage for the Trump campaign in 2016.

McConnell’s own efforts to increase the influence of big money donors in elections has paved the way for the increasing influence of Super PACs and 527 groups in the aftermath of the Citizens United decision, which have reduced the role that parties used to play in promoting moderate, electable candidates. Meanwhile, Gingrich’s efforts to erode the power of committee chairs, once used as a reward for loyalty and offering the prospect of career advancement, also lead to a reduction in the use of legislation pushing as a way to achieve prominence. This has contributed to the increasing number of legislators like Ted Cruz who use media savvy and big personalities as ways to achieve prominence with institutional routes to power being constrained and made less worthwhile. These committee leadership positions not only ensured loyalty, they also ensured cooperation and reliability, the lack of which has further added to a sense of “chaos syndrome” in Congress like the situations described above by Angus King and Lamar Alexander. Elections, both congressional and presidential, are increasingly rewarding activist candidates in primaries and those most capable of showcasing big personalities rather than effective legislation or policy formulation. The 2018 midterms have also shown that nationalizing elections is something that is not going away as parties increasingly align along racial, ideological, and again, geographical boundaries. It is no wonder, given the erosion of power in the governing institutions in Congress, that these trends are accelerating and will likely be with us for some time.