The Other Owen Andrews: An Interview With A Maryland Hoo, Green Party Lt. Governor Candidate

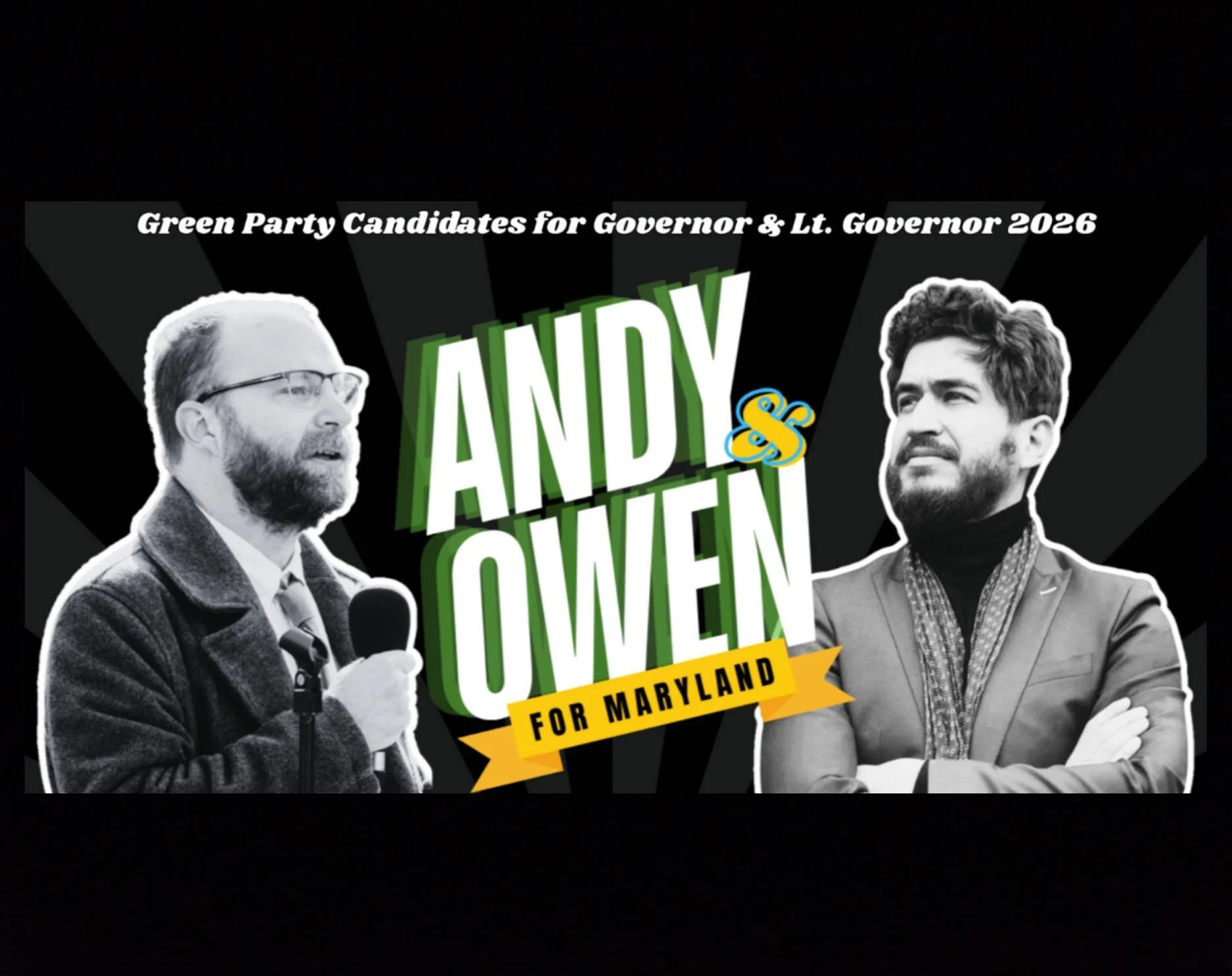

Image from https://www.gogreen2026.com/

I first came into contact with the other Owen Andrews through sheer, inconvenient happenstance: I had been receiving emails from UVA’s graduate school of education on programs well beyond my 18-year-old, fresh-out-of-high-school understanding. Later that year, my friends would go on to spot an “Owen Silverman Andrews” on the anonymous uvalentine messaging page whilst attempting to mess with me, accidentally sending messages to his inbox this time. Ultimately, it took until winter 2025 for us to message one another, and I am thankful that we did, because this interview was finally made possible.

Owen Silverman Andrews has worked in education and activism spheres for over a decade and is running for Lieutenant Governor of Maryland alongside Green Party candidate Andy Ellis in the 2026 election. His background has primarily been in teaching English language learners, and he is currently pursuing a doctorate of education at the University of Virginia. I conducted this interview by sending Owen my questions over text.

Owen Emmett Andrews: To ask this right off the bat, why the Green Party? And for any folks reading who aren’t familiar, what does the Green Party stand for?

Owen Silverman Andrews: The Green Party is the party most closely aligned with my values and policy priorities. The Green Party stands for social justice, peace, ecology, and grassroots democracy, which are its four core pillars. Decentralization, community-based economics, feminism and gender equity, respect for diversity, personal and global responsibility, and future focus and sustainability round out our ten key values. In addition, my grandfather Abe Silverman was a third party mayor of Sedalia, Missouri in the 1950s and 60s. Making change the hard way is a family tradition.

To go a little bit deeper and more personal, as an undergraduate, I studied Latin American history and political science. So, while I was initially excited about the change promised by the Barack Obama campaign—the first presidential candidate I was old enough to vote for—U.S. support for the 2009 coup in Honduras dimmed this excitement and led to my first involvement with street protest. For the next few years, I prioritized direct action and mass mobilization as means of making positive change. When anti-democratic and anti-socialist rigidity within the Democratic Party was revealed in Bernie Sanders’ 2016 presidential primary defeat, I changed my registration to Green. I added left third party electoralism to my grassroots organizer toolkit, and have found it a useful way of applying pressure, holding the powerful accountable, influencing the public narrative, and ultimately altering outcomes.

Emmett: What structural features do you think work against third parties? And in what ways can they succeed within our current political system?

Silverman: Third parties have been a consistent feature in U.S. politics. They’ve been an electoral expression of social movements for emancipation, suffrage, labor, and climate. The historical features that most work against third parties include elites’ alignment with the duopoly as manifested through big money in politics. Since the mid-1990s, Democrats and Republicans have also worked to exclude third party and independent candidates from debates, with mainstream media, and public television in particular, following suit. To address this, my running mate Andy Ellis and I have worked with a coalition to introduce a bill in the state legislature this year to pressure Maryland Public Television to include all ballot-qualified candidates for statewide office in their debates. That would allow voters to become more informed about their choices.

Third parties succeed within our current political system by identifying and agitating around specific pressure points. These points, often related to egregious injustices, are not being addressed by inside, access-oriented advocacy organizations. A couple examples are instructive. In the early 2000s, Green mayors performed gay marriages despite threats from Democratic attorneys general. More recently, we ran gubernatorial and presidential candidates whose platform prominently featured the Green New Deal. Both policies were quickly picked up by Democrats. This appropriation by the major parties is both evidence of the success of third parties and a structural feature which works against us. Only when both major parties refuse to appropriate a radical, urgent, and necessary position—as with the Democrats and Whigs with the question of emancipation and enslavement in the mid-19th century—is a third party likely to supplant a major party in U.S. politics.

I’ll point out that students are hungry for this conversation. The Review specifically has had a number of great articles recently on the need for and strategy behind supporting third parties. We are well aware the politics we’ve inherited aren’t serving us. It’s only browbeating by those with access to top down power that holds more people back from joining us in pushing for structural change. But the status quo grows more indefensible by the day. So, you have to ask yourself, am I ready to try something different?

Emmett: Are you concerned about the potential of third parties to split votes?

Silverman: Parties and candidates must earn our votes. That’s a bedrock principle of democracy. The threat of third parties earning votes keeps major parties accountable to their flanks. The less accountable they are, the greater the threat. More parties means more points of competition for voters and more respect for ideological diversity and heterodoxy. But elites, who enjoy the benefits of the status quo, would rather the major parties only compete in the center of the ideological spectrum, and so they push narratives about splitting votes and spoiling outcomes. These judgemental narratives can actually act to suppress participation in elections when people stay home rather than vote for a mainstream candidate who doesn’t share their values or priorities.

In the case of my lieutenant governor (LG) campaign, the incumbent governor-LG slate won in 2022 by a 32 point margin and is not facing an active challenge in the Democratic primary this time around. This gives activists fewer ways to pressure them on specific policies, from rising utility bills, to sprawling data centers, to proposed cuts to public education. Our Ellis-Andrews campaign is a vehicle for activists to hold Governor Moore and Lieutenant Governor Miller accountable for tacking to the middle and cozying up to corporate interests.

We know every vote for us is a vote we earned. We don’t take a single one for granted. If Democrats and Republicans felt they had to earn each vote, they would be more responsive to their constituents. Instead, they talk about splitting and spoiling, despite high dissatisfaction with the two party system. A positive contrast to their judgemental fall-in-line politics is a vision of a healthy multiparty democracy.

Emmett: What would governance look like in the case of a Green Party victory, especially in an otherwise two-party government?

Silverman: We would declare climate, food, and water emergencies to ensure state and local governments can urgently repair, replace, and reinvest in infrastructure. These are all areas where we want to build up through our local solidarity economies platform plank by investing in workers, co-operatively owned businesses, and community-based groups to address the root causes of crime, violence, and poverty.

Our commitment to healthcare and housing as human rights would be paid for by divesting from war, exploitation, incarceration, and environmental destruction. This includes ending longstanding subsidies in Maryland for weapons manufacturers and polluters. We would use that money to pay reparations and invest in community-led repairs. And we would fully fund our public education system and our public transit network.

When third party candidates have been elected governor or mayor in the U.S., they face both unique challenges and opportunities. They are able to govern differently because the incentives for collaboration with members of the other parties in the legislature increase, relative to the dysfunction we see in Congress and divided state capitals across the country. Bipartisanship is tired, but multipartisanship holds great future promise.

Emmett: What does debating mean to you? In what ways do you think that debate practices are important to a healthy democracy?

Silverman: Inclusive, well-structured debate is vital for the health of our democracy, whether it’s on Grounds, online, or on television. However, in a duopoly, debates are often predictable and constrained. Candidates and campaigns are focused on how their message will be interpreted by professional pundits and a narrow sliver of moderate voters. Candidates don’t speak much to each other’s bases, which they perceive as unreachable. By contrast, in a multiparty debate, there is both political and governing incentive to take more complex positions, because the point of convergence or conflict isn’t a singular midpoint, but rather occurs at multiple points along the political spectrum.

The benefits of improved debates for our democracy is why my running mate Andy Ellis and I worked with a state legislator from another party to introduce a bill this session that would pressure Maryland Public Television (MPT) to include all candidates appearing on the general election ballot in their gubernatorial debate MPT hosts. Please sign our petition! Public media is being attacked and defunded by the right based on mostly inaccurate claims of liberal bias. By including us and other third party and independent candidates in the debates this fall, MPT can push back on this narrative, staying true to its mission to inform voters of their choices.

Emmett: How will your doctoral work in education translate to the campaign trail?

Silverman: In my doctoral work at UVA and my day job work at a community college in Maryland, I’m focused on improving education for multilingual English learners. These students are immigrants or the children of immigrants. Obviously this is an incredibly difficult time to be an immigrant or the child of immigrants. My students and their families are being terrorized by ICE. But they’re also too often being systemically devalued by schools, school systems, and state and local politicians.

Since 2022, I’ve benefited from the applied nature of the Ed.D. program to publish a book, a peer reviewed journal article, and numerous commentary articles that address real problems and provide real solutions. And I’ve organized to put these solutions into effect, including being the lead advocate on the passage of the Maryland Credit for All Language Learning Act of 2024. This state law requires students studying English as a new language to receive college credit for their work, just as students do for Spanish, Mandarin, or Arabic. It’s an example of tripartisanship in action!

But there are limits to what’s possible within our current politics and the duopoly. My campaign for lieutenant governor is about expanding the public conversation and policy debate in order to change what’s possible and bring material benefits to communities across Maryland, including my students’. Our opportunity as students engaged in critical inquiry is to diagnose structural problems, identify radical solutions, and then organize to make those once seemingly impossible solutions possible. That’s what my campaign is all about, too.

Emmett: What has your involvement in campus activism been like? What political lessons have those experiences provided you?

Silverman: As an off Grounds, part-time grad student in a mostly asynchronous doc program, I’ve had to hustle to find community on Grounds. But it’s been so worth it!

I’ve been involved with organizing to get UVA off fossil fuels through DivestUVA (now a Sunrise hub). I’ve been a part of a Palestine solidarity teach-in series, circulated a petition calling for charges to be dropped for those arrested at the encampment in 2024, and participated in a critical whiteness study group. And I’ve also done some nerdier online activism to get U.S. News & World Report and Wikipedia to stop using the former Confederate name of the School of Education & Human Development. These experiences, relationships, and wins are every bit as much a part of what I’ve learned at UVA as my coursework.

These experiences reinforce that international solidarity must be locally rooted, the past is ever present, and the future belongs to the people. I look forward to continuing to be involved in activism for social justice on Grounds during my last couple years in my doc program and beyond.

Emmett: What advice do you have for readers who are interested in political involvement?

Silverman: This is such a fun and important question! My primary advice is: show up for the issue you care about, stay for the people who care for you and each other. Like any other social space, political spaces can be constructive or toxic. You can try different spaces until you find that alignment between cause and vibe.

In addition to issues and relationships, it’s also important to consider decision making process and organizational structure. Does the group have an agreed upon and transparent way of planning and doing political action? Is there a rigid hierarchy or a consensus-based approach?

Lastly, I would encourage you all to consider the importance of respect for diverse tactics, tone, and timing in movement formations for social change. Being aligned on values and priorities often isn’t enough. Durable coalitions also benefit from an agreement to disagree on members’ methods, communication styles, and urgency while still working together to achieve shared priority outcomes. These dynamics are incredibly important to check in about regularly, and by doing so, you and your organizing partners can often avoid schisms that would undermine progress toward shared visions for the future.