The Year of the Union

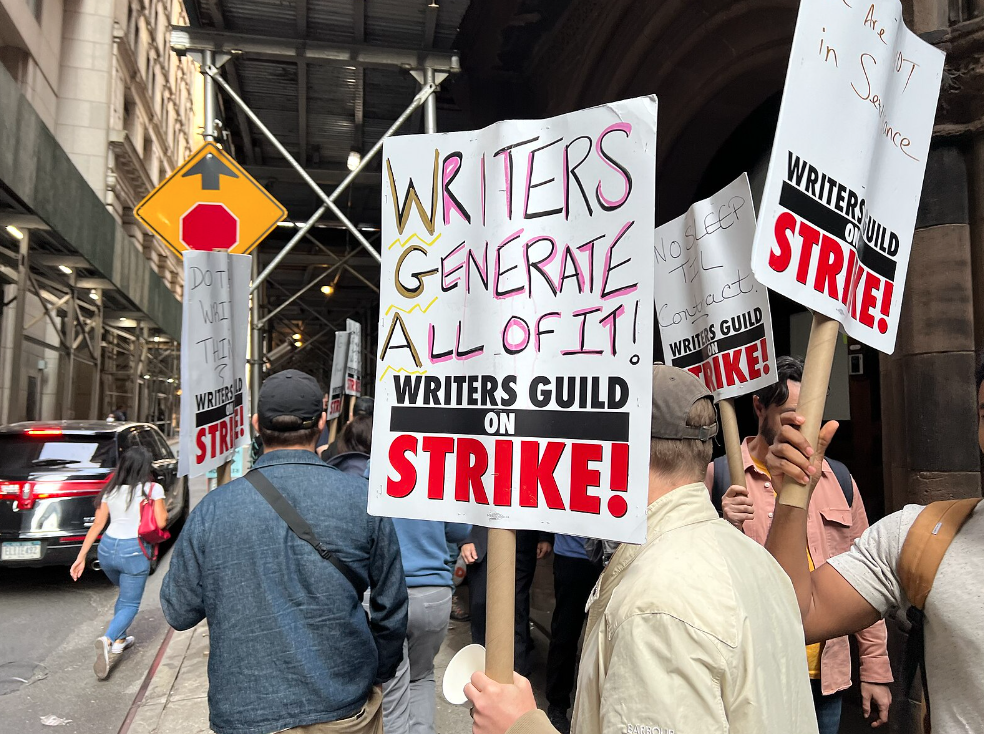

"Writers Guild of America 2023 writers strike" by Fabebk is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

The past few months have seen actors from all areas of the film industry come together to protest the unfair contract offered to the Screen Actors Guild (SAG) by the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP). Celebrities from Leonardo DiCaprio to Margot Robbie were seen on the picket lines demanding further negotiation of the AMPTP contract and objecting to the treatment of SAG members by the industry. The strike ended on November 9th, coming at the relief of the actors whose livelihoods were suspended under the strike conditions. SAG was not the only major union to go on strike in 2023. The Writers Guild of America (WGA) and the United Auto Workers (UAW) also went on strike recently, protesting corporations in favor of improved contracts. 2023 has seen more striking than the past few years combined, and importantly, the unions seem to be emerging victorious. What spawned this “year of the union” and why is it yielding such success?

A union is generally defined as an organization within a workplace that works as a team to have a voice in the workplace. They use their power as a group to advocate for changes to be made within the company, often pertaining to salaries or benefits that would improve the conditions of the workers. In this way, unions act as arbiters of collective bargaining. When a union goes on strike, the corporation loses vast amounts of money, necessitating renegotiation which often leads to improvements for workers. However, these big companies are much wealthier and more dominant than the unionized workers, creating a power imbalance. A tactic used by these companies in order to combat the high demands of a union is to simply wait it out. They assume, often correctly, that the longer a strike continues and the unionized workers remain unpaid, the more willing the workers will be to concede on their demands. The AMPTP infamously stated in July that they would not put an end to the strike until the writers start losing their apartments – a truly evil sentiment from the studios that rely on the work of actors.

SAG, WGA, and the UAW took huge risks in striking. Thus, they believed the benefits of the renegotiation would heavily outweigh the losses that could be incurred through the union. Across the unions, workers mobilized in protest of insufficient labor protections and low pay, and the companies listened due to the leverage created by the low unemployment rate that makes it hard to replace workers.

The Writers Guild of America strike began in response to the renewal of the contract held between the WGA and the AMPTP. The WGA wanted to add additional protections for writers – such as increased compensation and pensions – as well as improvements to the size of writing teams, better residuals, and protections against use of artificial intelligence. Considering that a contract of this kind would mean a huge loss of profit and power for the AMPTP, the studios countered the demands of the WGA, thus ushering the workers into the strike. In late September, after months of back-and-forth conflict over the negotiations, the two committees reached a deal that ensured many of the demands of the writers at the loss of the studios.

In the past, a deal like this seemed out of the question due to the sheer amount being given up by the studios. It would not have been possible without the pressure put on the AMPTP by the writers, who the studios realized they needed to keep the business alive, and the overwhelming popular support that the WGA received from the American public. President Biden himself congratulated the writers upon their victory, acknowledging the power that a union can have over large corporations. The conclusion of the strike was likely also aided by the negative financial impact felt by large studios like Sony, who reported a loss of profit at the end of the term.

A little over two months after the WGA went on strike, the Screen Actors Guild began their strike, also against the AMPTP. The Guild voted unanimously to strike in hopes of negotiating a better contract with the studios that would enshrine their rights to proper payment and expanded benefits. Their strike concluded on November 9th, with SAG and the AMPTP reaching a tentative deal that again ensured many of the wants of the Guild and forced concessions for the studios. It marked another win for unions, with the deal being dubbed as “industry-breaking” by many in Hollywood who see it as a huge victory for the actors over the studios.

In a completely different sector, the United Auto Workers also embarked on a strike in mid-September that derailed the automobile industry before a deal was reached. The UAW organized strikes against the Detroit “Big Three” automakers: General Motors, Ford, and Stellantis. There were 150,000 workers with a vested interest in the success of the renegotiation, which hinged on wage raises and increased retirement benefits. The new contract will come at a huge financial cost to the automakers due to the increased labor costs. One of the leaders of the UAW bragged that they had, “squeezed every last dime out of General Motors.” The automobile companies were forced to yield to the demands of the union due to billions of dollars of revenue loss caused by the walkouts. Additionally, the labor market is surprisingly sparse, as is indicated by the record low rate of unemployment. This put the auto companies in a tough situation: The lack of skilled labor available to counteract the effects of the strike meant they had no choice but to negotiate with the union. Similar to both the WGA and SAG strikes, the UAW strike received widespread media attention and support from members of both political parties. In a historic moment, President Biden visited the picket lines in Detroit to support the union workers, marking the first time a sitting president ever participated in a strike.

In light of these three historic and sweeping victories for workers across America, the popularity of unions has only grown. A recent poll suggests that sixty-one percent of Americans support unions and believe that they do good for the economy. These widespread wins for laborers are indicative of changing attitudes within the country, where workers are more inclined to test the limits of the companies they work for if it might mean improving their employment benefits or wages. The reasoning behind each of these decisions is the same: There is a lack of skilled labor available in the United States. The workers are in a position with leverage over companies who are forced to agree to their demands in order to keep business running. The Hollywood studios had to consider that the entire film industry would be obsolete without actors and writers. In a similar manner, Detroit’s Big Three found that their unionized workers were more difficult to replace in such a depleted labor market, and that perhaps keeping them at a higher cost was worth it in the long term if it meant ending the strike.

Unions seem to be paying off for workers nearly universally, sometimes even with the mere threat of a strike motivating raises and change within the company. This phenomenon was seen in the Teamsters union, which organizes freight drivers and warehouse workers, in August. An overwhelmingly large strike of UPS workers was narrowly avoided thanks to the passing of a new contract that guaranteed raises and increased base pay for workers across the US. In this case, the workers didn’t even need to formally strike for their demands to be met and taken seriously. Union members across industries are becoming empowered to take their futures into their own hands rather than leave it up to an ambiguous and disappointing contract.

Despite this progress across the workers unions and general support for unionization, the membership rate of workers in unions has been on the decline for decades, reaching a new low in 2022 at 10.1%. The 1950s saw one-in-three workers being represented by a union, while today a mere one-in-ten are. This is partially due to “right to work” laws being passed in two dozen states – which make the path to unionization more difficult – in addition to companies spending hundreds of millions of dollars on anti-union consultants. Some ways that these efforts can be counteracted to boost union membership is through encouraging new workers to join by communicating benefits provided by the unions and open conversations with active union members. If new workers can understand what a union can do for them, they might be more inclined to join despite the hurdles placed in their way by governments and corporations.

Considering the progress made by unions within the past year, the companies clearly have a reason to be afraid of the power of unions: They can completely derail entire industries if their demands are not met. The recent strikes have set a hopeful standard for other industries, inspiring strikes for airline pilots and healthcare workers alike. In an ideal world, the younger generation will see these successful strikes as reasons to support and join a union, thus building a society that has the power to protest unjust payment and treatment. The right to unionize is like the right of the branches of government to check one another: To go unchecked leads to infringements on liberties and unbridled power, which begets corruption. I hope that this unprecedented year of the union is just the beginning.