The Digital Panopticon: How Online Communities Enforce Conformity

How much do you monitor your social media feed? In 2021, social media use claims an increasingly large part of our social lives. According to the Pew Research Center, 7 out of 10 Facebook users claim to visit the site at least once a day, with 49 percent claiming to use it several times per day. Political engagement in online spaces is equally high: 54 percent of young adults claim to have used social media to engage with political activism in some way. While this may seem like a benefit of our growing digital landscape, political engagement online is not without its drawbacks. Political involvement online, in both liberal and conservative spaces, encourages conformity with peers and serves to politically isolate and radicalize individuals into subsets of their communities. Since there is no space for them to voice a dissenting opinion, these community subsets can quickly form insular groups that fail to recognize outside influence.

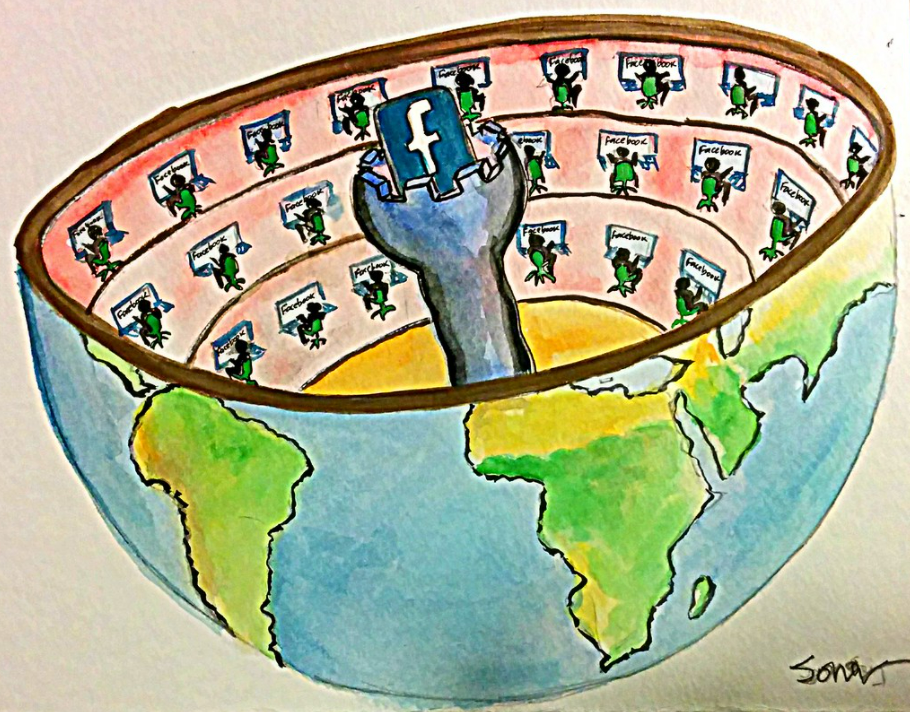

The idea of a panopticon is seemingly far removed from Web 2.0, but when we examine the concept more closely, startling similarities emerge. Originated by Jeremy Bentham as a model of a perfect prison system, the panopticon’s architecture ensures constant, permanent visibility, such that power is automatized and no force is necessary to maintain control; simply being watched is enough to enforce conformity. However, as we move further into the digital age, a panopticon looks less like a prison and more like something familiar: social media.

As much as you may monitor your feed, your feed monitors you. It’s no secret that websites like Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube collect personal user data and then sell it. Even apps targeted at children, such as TikTok sell user’s data to the highest bidder. Social media sites have access to your browser history, your activity, and even your biometrics— and that’s not including whatever information you choose to post online. On top of that, millions of other users have access to your personal feed. While it is not necessarily a prison, social media certainly has the architecture of a panopticon. However, according to Anders Albrechtslund, a modern surveillance theorist, social media differs from a panopticon in one major way: participatory surveillance. People voluntarily act as both the watcher and the watched, and being both visible and accessible is a precondition for participation.

Although this power structure is not inherently dangerous to social communities, it can become oppressive and hostile in communities centered around politics. Social media such as Reddit or Twitter, which are two of the largest hubs of online political activity, have a hierarchical organization of users, where some members of these communities gain privileges based on follower count or popularity. They can gain anything from a blue checkmark to differentiate their account from other people’s, to the ability to moderate the community of which they take part. Eight out of the ten most followed accounts on Twitter are celebrities, who gain massive social influence through their popularity on the site. By establishing certain members as de facto thought leaders based on popularity alone, social media sites encourage communities to center around the beliefs of these leaders and makes little room for dissenting opinions from people who aren’t privileged in the same way. The conditions inherent in many social media communities foster groupthink, which can have disastrous implications in a political sphere.

Groupthink occurs when an in-group forms a group norm, where deviation from that norm is met with intensive pressure to return to conformity or expulsion from the group entirely. In a harsh political environment, the pressure to conform contributes to stagnation of political ideas, as well as an increased conformity to ideas with which people may not necessarily agree. Groupthink discourages critical thinking and radicalizes communities by disallowing dissenting voices to be heard—there is no room for a voice of reason in the in-group. Groupthink pressure to conform, combined with constant surveillance from other community members, essentially forces people to adopt the prevailing ideas of their community’s thought leader, and shun the ideas of any out-group members. As individual communities grow more and more radical, there is less room for overlap between different groups, isolating people politically from anybody outside of their chosen group, which, in turn, increases social pressure to remain within an in-group. Not only do online communities suffer from increasing polarization and radicalization, they also suffer from an inability to detach from their group once they are accepted, leading to a vicious cycle of online isolation.

Groupthink online can have disastrous repercussions in the real world as well. The Capitol riots this January were one of many examples of an online extremist group growing so insulated from out-group influence that they failed to understand the radical nature of their own actions. In a process that would make Foucault weep, digital communities create their own microcosmic panopticon.

So, how do we combat the effects of participatory surveillance and groupthink? Disconnecting from social media entirely would solve the issue, but in an increasingly digitized world, this solution isn’t the most feasible. On an individual scale, a more manageable way to counteract the effects of participatory surveillance and the persecution of out-group ideas is to develop a greater sense of empathy towards people online. By allowing members of your community to simply not conform, you discourage an environment that facilitates groupthink and help invite outside influences into your in-group. Despite working in a panopticon, we can all work to ease the pressure by taking one less pair of judging eyes off of our digital neighbors.