‘My Body, My Choice’ Beyond the U.S. Mainland

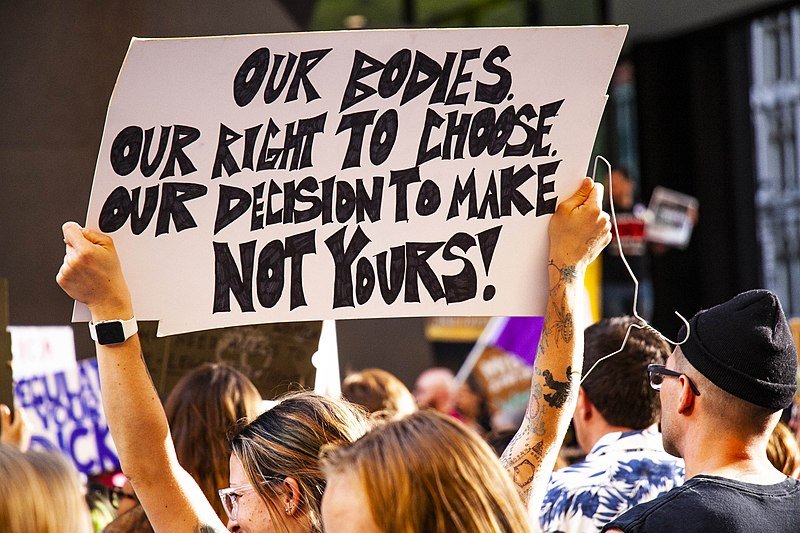

Photo by Charles Edward Miller is licensed for use under CC BY-SA 2.0.

The U.S. Constitution grants all women the right to an abortion, but the fineprint says otherwise. The U.S. territory of Guam currently houses a female population of 84,537; yet, as of 2018, there are zero abortion providers on the island. It costs women upwards of $1,000 and an eight-hour plane ride to access the service. This public health disparity is even more problematic because Guam has the second-highest number of sexual assaults per capita in the country. Even though the right to reproductive freedom has been at the forefront of American mainstream media coverage for the past several years, public discourse is centered around the rights of women living on the mainland. To achieve total reproductive justice, the abortion conversation must address the inequality from an intersectional approach, one that includes the bodily autonomy of women living outside of the U.S. mainland.

Luckily, this past September, a federal court case removed the need for women to travel out of Guam for abortion pill prescriptions. After several lawsuits brought by the American Civil Liberties Union, Guam is slowly but surely making legal progress in the right direction. The ruling introduces “tele-abortions,” a remote method for women to connect with doctors, where they can provide consultations over video conference. Still, this case illuminates the glaring absence of essential health care infrastructure in Guam and, subsequently, other U.S. territories that similarly lack autonomy and representation in the federal government. Without just and equitable policies, women in Guam and other U.S. territories will never have affordable and accessible reproductive health resources to live the highest quality of life possible.

The relationship between Guam and the U.S. federal government resembles that of a conservatorship dynamic. Even though the residents of Guam are considered U.S. citizens, they do not have the right to vote in national elections. However, voters caucus during the presidential primary. In addition, The Organic Act (1950) allows for the popular election of a governor and lieutenant governor who hold office in four-year terms. Guam’s local legislature is a unicameral body with 15 senators who are elected for two-year terms. Despite having its own distinctive characteristics as a constituency compared to the U.S. mainland, Guam’s representation in the U.S. federal government exists as only one elected delegate to the House of Representatives who holds office for two years. Moreover, the delegate cannot vote on the final passage of legislation. The barring of self-determination and limited autonomy in the United States’ national governing bodies leaves Guam with little space to address the policy issues, some of which are created and exacerbated by the United States itself.

According to a 2018 Kaiser Health Care survey of employer-sponsored health care benefits, the annual health care cost for a single person on Guam is about $3,180, compared to $6,690 in the States. The family coverage on Guam is $9,540 compared to the annual average of $19,616 in the States. Moreover, the average poverty rate of Guam is 22.5 percent (2010), which is a little over double the U.S. mainland’s average poverty rate of 10.5 percent (2019). Logically, Guam should receive the most support from federal Medicaid policy, a federal insurance program targeted towards low-income individuals. However, the obstacle is that Medicaid is a fixed, capped allotment to U.S. territories, meaning the U.S. government is not technically mandated to fund Guam’s Medicaid services past a certain threshold—a threshold that is already dangerously low. The U.S. government has haphazardly provided for Guam’s health care because U.S. territories’ funding is not an entitlement and is not tied to the income levels or health care needs of the population.

Though there has been little to no reform in how the federal government has disbursed crucial healthcare funds to its territories, grassroots activists in Guam and beyond have been committed to affecting change locally. As women of color in the U.S. mainland have championed the movement against anti-abortion politics, so have the women of color in Guam. Indigenous women from the island’s most prominent ethnic community, the Chamoru, are leading life-changing projects to implement policies and laws that allow for comprehensive reproductive healthcare, easily accessible contraception, and robust sex education in Guam’s public schools. Furthermore, the local reproductive justice initiative, Famalao’an Rights, has worked tirelessly with the ACLU on filing two lawsuits against abortion restrictions on the island. The aforementioned federal court case has been one of the most monumental legal victories since the end of Guam’s full abortion ban in 1990. However, in order for the federal government to commit to a healthier and more sustainable relationship with Guam, it must support Famaloa’an Rights and uplift the island’s health care infrastructure through adequate funding.

Now, the U.S. government must confront the failure of its conservatorship over its territories. The lack of quality health care infrastructure in Guam is an opportunity to reimagine the United States’ relationship with its territories. The future of Guam’s population and other U.S. territories' livelihoods rests on the diligence of its governing body to listen to its people whose demands remain overdue.